Key Takeaways

- Lawmakers approved a special session to redraw Missouri’s congressional map.

- The plan splits Kansas City into multiple districts to create a new GOP-leaning seat.

- Democrats call the move unconstitutional and promise legal challenges.

- Supporters say the map meets legal rules and will boost Republican seats.

Missouri lawmakers moved fast this week to approve a new Missouri congressional map. They called a rare mid-decade session to redraw district lines. Supporters say it balances populations and follows the state constitution. Yet critics accuse Republicans of gerrymandering for political gain.

Why redraw now?

Just three years after the last census, Missouri’s GOP leaders pushed for a new map. They say the state population has shifted and needs fresh lines. However, Missouri law requires redistricting only once every ten years, after each census. Opponents argue this special session breaks that rule.

Furthermore, President Trump urged GOP-run states to redraw maps ahead of next year’s midterms. Trump praised the proposed map as “perfect” and urged lawmakers to pass it “as is.” Even so, Republicans in Missouri insist the governor’s staff drew the map, not the White House.

Because Democrats hold just two of Missouri’s eight House seats, Republicans see a chance to expand their majority. Under the new plan, GOP leaders hope to hold nearly seven districts. Critics call this a blatant power grab that undercuts fair representation.

Missouri congressional map and the GOP push

Under the approved proposal, Kansas City’s east side stays in the 5th District. Yet most of the city splits into other districts. For example:

• Downtown Kansas City moves to the 4th District, stretching south almost to Springfield.

• Neighborhoods north of the Missouri River join the 6th District, reaching to Iowa and Illinois.

• The 5th District picks up rural counties east of the city, including Jefferson City.

By carving up Kansas City, Republicans aim to dilute Democratic votes. Supporters argue the new Missouri congressional map keeps districts compact and contiguous. They claim it divides fewer communities than the current lines. They also point out the new map adjusts populations precisely, as required by law.

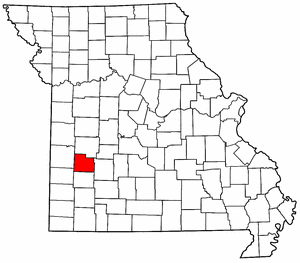

Moreover, the plan leaves two solidly Republican districts—the 7th in southwest Missouri and the 8th in the southeast—untouched. It tweaks the 1st District around St. Louis slightly but focuses most changes on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th districts.

Because the governor called lawmakers back into session, they had just a few days to review public input. Opponents say this rushed timeline cut communities out of the process. They worry the map serves political interests over voters’ needs.

Legal challenges and lawsuits

Immediately after the vote, Democrats and civil rights groups vowed court challenges. They argue the special session itself violates the Missouri Constitution. That document says redistricting happens only once per decade after a census.

Additionally, critics claim the map relies on outdated population data. They say this may break state and federal rules requiring equal representation. The Missouri NAACP filed a lawsuit in Cole County, calling the special session unconstitutional. U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver also plans to challenge any gerrymandered map in court.

Democratic legislators called for more detailed demographic data before approving changes. They argued transparency is vital for fair elections. However, Republicans refused to share all the numbers, saying the map already meets legal tests.

The battle will likely head to Missouri’s Supreme Court or federal court. That process could delay implementation until after next year’s elections. Meanwhile, voters remain unsure which districts they will join.

What’s next for the map?

The Missouri House plans a full debate on Monday. If approved, the Senate will vote Tuesday. Then the governor can sign the new Missouri congressional map into law. Yet court fights could halt its use in upcoming primaries and the 2026 general election.

Lawmakers on both sides say they will not back down. Republicans insist they followed rules and aimed for fair districts. Democrats argue voters deserve genuine representation, not political tricks. As a result, the state faces weeks of hearings, amendments, and legal filings.

Regardless of the outcome, this fight highlights the power of redistricting. It shows how map lines can shape election results for a decade. Voters and advocacy groups across Missouri will watch closely as the debate unfolds.

FAQs

What is the new Missouri congressional map about?

The new map splits Kansas City among several districts to create a stronger Republican advantage. It redraws lines in five of the state’s eight districts.

How does the proposed map change current districts?

Under the plan, downtown Kansas City moves to the 4th District, areas north of the river join the 6th District, and the 5th District picks up rural counties east of the city.

Will the new map face legal challenges?

Yes. Democrats and the Missouri NAACP filed lawsuits, arguing the special session violates the state constitution and the map uses outdated census data.

When could the new map take effect?

Lawmakers aim to approve it this week, but court battles may delay its use until after the 2026 elections.